The Fatal Flaw of Watchmen

The Fatal Flaw of Watchmen (the movie)

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ 1986 graphic novel “Watchmen” is, in my opinion, the greatest comic book of all time and possibly one of the greatest books of all time. The story is a deconstruction of the superhero genre as comic books moved from their Bronze Age to the Modern Age. The book was incredibly important in the evolution of comic books, from magazines meant for children to mature and variable storytelling devices that could appeal to all ages. It’s an incredible and shocking work of art, both in its gorgeous, yet sometimes horrifying, visuals and intricate character work that provides everyone in the book with a fleshed-out personality. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of “Watchmen” is the condemnation of violence and how violence is masterfully paced, factors the 2009 film adaptation neglected entirely.

One of the many expertly done aspects of “Watchmen” is Moore and Gibbons’s portrayal and use of violence.

Violence in “Watchmen” is never cool, satisfying, or even nice to look at. It’s genuinely sickening and sometimes tragic to see. “Watchmen” is known for being one of the most violent comics ever written, but it was the well-paced violence of Moore and Gibbons that made it revolutionary. For most of the book, the violence is mainly in flashbacks, with some key exceptions such as Rorschach’s prison escape or when Dan and Laurie are confronted in the alleyway by thugs. The violence builds up and gets more intense until it reaches its climax when a giant “alien” squid is teleported to New York City, killing millions. Six full-page panels are filled with nothing but death and destruction. It is a truly horrible sight and an incredibly effective one at that. The book’s portrayal of violence as deplorable and circular in nature is what gives the book its heart. It is a never ending cycle of pain that leaves shoddily-built “peace”. If you are adapting “Watchmen,” under no circumstances should you ever change the way violence is portrayed.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what director Zack Snyder did. Snyder’s Watchmen was released in 2009 to mixed reviews, though I don’t understand what positive aspects critics found. It is a massive dumpster fire, butchering everything that made the comic great. Characters like The Comedian — a monster who murders a pregnant woman and tries to rape the original Silk Spectre – are turned into “awesome” and “super-cool” broken people. Rorschach is no longer a misogynistic, racist, homophobic nutjob, but rather an anti-hero who’s justified in the horrible things he does and says. The only thing Watchmen has that’s remotely good is the visuals, but that is the surface level of the movie. All subtlety has either been thrown out or is so heavy handed, a sledgehammer would have more nuance. But the cardinal sin that this adaptation makes is in the depiction of violence. Snyder glorifies every punch thrown and every bit of blood spilled, completely contradicting the novel’s messages about violence. He turned villains into heroes, violence into enjoyment, and a masterpiece into garbage.

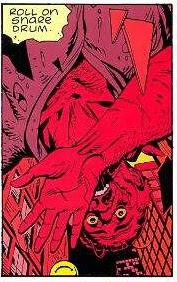

Let’s start with how Rorschach’s backstory is glorified. After being captured by the police in Chapter Five, Chapter Six focuses entirely on Rorschach’s psyche and reveals his origins. This is expertly done all from the point of view of Rorschach’s psychiatrist, Malcolm Long. An outsider’s perspective on the character of Rorschach is incredibly important, because up until now he had been the main point of view for the story. With this new perspective, Rorschach’s violence becomes sickening and there’s a more sadistic side to him revealed to the reader. During his sessions with Long, Rorschach reveals his transformation from his birth name of Walter Kovacs to the identity of Rorschach in a truly horrifying account. After investigating the kidnapping of a young girl, Rorschach finds to his horror that she was murdered by the kidnapper and the body was disposed of by two dogs. During this retelling, he describes the moment he kills the dogs as “Shock of impact ran along my arm. Jet of warmth spattered on chest, like hot faucet. It was Kovacs who said ‘mother’ then, muffled under latex. It was Kovacs who closed his eyes. It was Rorschach who opened them” (Moore and Gibbons, Iss. 6, 21). Rorschach was born from violence, and lives in it from that moment forward. This is followed by one of the most sadistic moments in the book when Rorschach kills the man by setting his apartment building ablaze. Rorschach just calmly watches the inferno for three whole panels, his transformation cemented. In just this one chapter, we no longer view Rorschach as an anti-hero fighting against a corrupt system and objective evil. He is the evil that he claims to hate. He is a monster, plain and simple.

Zack Snyder’s Watchmen takes a wildly different approach that sides with Rorschach and paints him as a hero. Despite a still brutal method in murder, the key difference is in how it’s depicted. The book makes it clear that

Rorschach is a monster, a cold blooded killer. He shows no emotion when he burns up the building, instead quietly watching his handiwork. The movie adaptation goes in a different and contradictory way to the book. Instead of an emotionless Rorschach coldly killing, this Rorschach hacks away passionately at this man’s head in an act of revenge. There’s a lot more emotion in this scene, and as a result, it humanizes Rorschach and makes him a tragic hero. That element of Rorschach as a cold blooded murderer is gone in this scene. Through this cinematic language, we side with Rorschach, especially when after he kills the man he says “men get arrested, dogs get put down” (Watchmen 1:30:30 – 1:30:36). That horror is lost and replaced with a sense of Rorschach being right in his methods, which is wrong at best and a very disturbed view of this character and the world at worst.

Rorschach isn’t the only character that Snyder messed up though, and that brings me to my second example of the over glorification of violence, The Comedian. Without a doubt, The Comedian (a.k.a Edward Blake) is the single most violent character in “Watchmen” and commits some of the most atrocious acts in the book. Violence is so vital to Blake’s character, but Moore didn’t make him a one-note ultra violent maniac. There is a lot more nuance to The Comedian’s character than is initially shown. Throughout “Watchmen”, Blake’s violence is rampant and horrific to view not only because of the act itself, but because of the way Blake revels in it. In Chapter Four when Dr. Manhattan reminisces on his time in Vietnam with The Comedian, he recounts the time with Blake by saying, “Blake suits the climate here: the madness, the pointless butchery… As I come to understand Vietnam and what it implies about the human condition, I also realize that few humans will permit themselves such an understanding. Blake’s different. He understands perfectly… …and he doesn’t care” (Moore and Gibbons, Iss. 4, 19). This is paired with two panels of Blake gleefully wielding a flamethrower, his face illuminated by the fire. This disturbing enjoyment Blake finds in inflicting pain is present in much of the novel, such as when he eagerly throws tear gas and fires rubber bullets on protestors in Chapter Two. The Comedian could easily be written off as a character with his indulgence in violence being all of him, but that view ignores the much more interesting trait of his reactions to violence against himself.

over glorification of violence, The Comedian. Without a doubt, The Comedian (a.k.a Edward Blake) is the single most violent character in “Watchmen” and commits some of the most atrocious acts in the book. Violence is so vital to Blake’s character, but Moore didn’t make him a one-note ultra violent maniac. There is a lot more nuance to The Comedian’s character than is initially shown. Throughout “Watchmen”, Blake’s violence is rampant and horrific to view not only because of the act itself, but because of the way Blake revels in it. In Chapter Four when Dr. Manhattan reminisces on his time in Vietnam with The Comedian, he recounts the time with Blake by saying, “Blake suits the climate here: the madness, the pointless butchery… As I come to understand Vietnam and what it implies about the human condition, I also realize that few humans will permit themselves such an understanding. Blake’s different. He understands perfectly… …and he doesn’t care” (Moore and Gibbons, Iss. 4, 19). This is paired with two panels of Blake gleefully wielding a flamethrower, his face illuminated by the fire. This disturbing enjoyment Blake finds in inflicting pain is present in much of the novel, such as when he eagerly throws tear gas and fires rubber bullets on protestors in Chapter Two. The Comedian could easily be written off as a character with his indulgence in violence being all of him, but that view ignores the much more interesting trait of his reactions to violence against himself.

Readers see a different side of The Comedian when he is on the receiving end of violence. The two most prominent examples would be when he kills his Vietnamese lover after she attacks him and his reaction to being murdered earlier in the series. The former takes place in the aftermath of America’s victory in the Vietnam War when Dr. Manhattan and Blake are at a bar. A woman who Blake impregnated demands that he stay in Vietnam and help raise the child, but Blake refuses and insults her and her country. In an act of retaliation, the woman slashes Blake across the face with a broken bottle, but is shot dead by him immediately after. This is a monstrous action, and it reveals Blake’s massive insecurities that he covers with violence. For all the pain and chaos he creates, The Comedian is an insecure man at his core. Violence towards others is ok, even enjoyable, but when it’s turned against him, his insecurities take over and manifest into violence, anger, and embarrassment. Even more evidence of Blake’s insecurities are on display in the beginning of the book, when he dies when thrown out of his high-rise apartment. Chapter One’s flashback into Blake’s death admittedly doesn’t provide much insight into his character, but it is in Chapter Two where a small yet significant panel shows his face right before he hits the pavement. The Comedian, a bloodthirsty maniac who used a mask and the facade of being a hero to indulge in his own twisted and sadistic pleasures, is scared. His face is full of fear as he realizes that it’s the end, that there’s no revenge or comeback he can make. At that moment, he’s just a scared old man who’s about to die. All he can do is fall and scream.

examples would be when he kills his Vietnamese lover after she attacks him and his reaction to being murdered earlier in the series. The former takes place in the aftermath of America’s victory in the Vietnam War when Dr. Manhattan and Blake are at a bar. A woman who Blake impregnated demands that he stay in Vietnam and help raise the child, but Blake refuses and insults her and her country. In an act of retaliation, the woman slashes Blake across the face with a broken bottle, but is shot dead by him immediately after. This is a monstrous action, and it reveals Blake’s massive insecurities that he covers with violence. For all the pain and chaos he creates, The Comedian is an insecure man at his core. Violence towards others is ok, even enjoyable, but when it’s turned against him, his insecurities take over and manifest into violence, anger, and embarrassment. Even more evidence of Blake’s insecurities are on display in the beginning of the book, when he dies when thrown out of his high-rise apartment. Chapter One’s flashback into Blake’s death admittedly doesn’t provide much insight into his character, but it is in Chapter Two where a small yet significant panel shows his face right before he hits the pavement. The Comedian, a bloodthirsty maniac who used a mask and the facade of being a hero to indulge in his own twisted and sadistic pleasures, is scared. His face is full of fear as he realizes that it’s the end, that there’s no revenge or comeback he can make. At that moment, he’s just a scared old man who’s about to die. All he can do is fall and scream.

What’s really irksome about Zack Snyder’s version of The Comedian is that he views the character in the exact opposite way Moore and Gibbons created him in the series. Now that’s not to say that Snyder condones murder or

sexual assault, but rather that he viewed The Comedian as a hero. The red flags are present from the very beginning of Watchmen when The Comedian is killed. Instead of this old man clearly being brutalized and scared for his life, he almost accepts that he’s going to die and even says that everything’s a joke before being tossed out the window. Instead of going out in a pathetic way, his death is this cool and edgy spectacle in slow motion. This core misunderstanding of the character continues throughout the film where he’s shown more as a hero and less as a monster. In the book, a flashback shows Nite Owl II and The Comedian suppressing rioters and The Comedian wears a bondage mask while doing this. The visual of him firing rubber bullets at rioters while wearing this mask is a clear indication of the pleasure and enjoyment he receives from others’ pain. This idea is completely abandoned in the movie, where no deeper layer is given to why The Comedian revels in carnage or what he gains from it. He just does because apparently violence is cool to Zack Snyder. His time in Vietnam is again shot in slow motion with him depicted as this heroic force, riding in to kill the Vietcong while “Ride of the Valkyries” plays in the background. It almost looks like military propaganda. When he kills the pregnant woman in the bar, instead of this embarrassment and anger surrounding him, he’s calm and collected. Instead of a monster hiding insecurities with atrocious violence, The Comedian is reduced to being a cool anti-hero we should feel bad for because he died. These small changes can end up making a viewer wonder if Zack Snyder even read “Watchmen,” because The Comedian presented as an insecure sadist is not subtext. It is the literal text.

My final example of where the film falls far short is an obvious complaint, but one that must be addressed. Of course I am referring to the replacement of the doomsday squid with an atomic bomb. This change fails for multiple reasons. From a story perspective, it makes no sense why world peace would be achieved after an attack on multiple countries by Dr. Manhattan, a superhero working for the American government. If anything, America would be blamed for all of the death and chaos that came from losing control of their weapon. Aside from failing as a plot

point, it also fails to capture any of the weight from the squid’s attack in the book. The reason the squid worked wasn’t only because millions of people died, but also because Silk Spectre II’s reaction when she and Dr. Manhattan teleported to its landing in NYC later. Bodies littered the streets, people tried to shield others from the blast to no avail, and this mysterious and frightening creature is the cause. This horrific image is shown for six whole pages so both Silk Spectre II and readers can sink in the extent of death and destruction. With the atomic bomb, sure people are shown being vaporized by the blast, but little time is given for the audience to realize how much death happened. There’s nothing that feels horrific with the bomb, which is a massive loss from the terror of the squid. Death feels almost throwaway throughout the entire film and the atomic bomb’s lack of tangible consequence cements that. Death in the book was real and frightening, even to nameless characters. The film has none of the depth in its world that the book did and as a result, all life lost feels disposable.

Zack Snyder’s Watchmen is a colossal mess when it comes to adapting the incredible source material. Its violence is disgustingly glorified and brutal monsters are shown as heroic figures. Please don’t watch Watchmen. It’s a horrible adaptation that actively spits in the face of fans of the source material and presents violence as cool and awesome. However, you should read the book “Watchmen,” since there are many, many amazing scenes with powerful messages I could never explain in-depth making it one of the most important graphic novels of all time.

Ed is a senior who is extremely interested in comics, movies, and horror films. He is very introverted and spends a lot of time writing, watching movies,...