Blood Orange

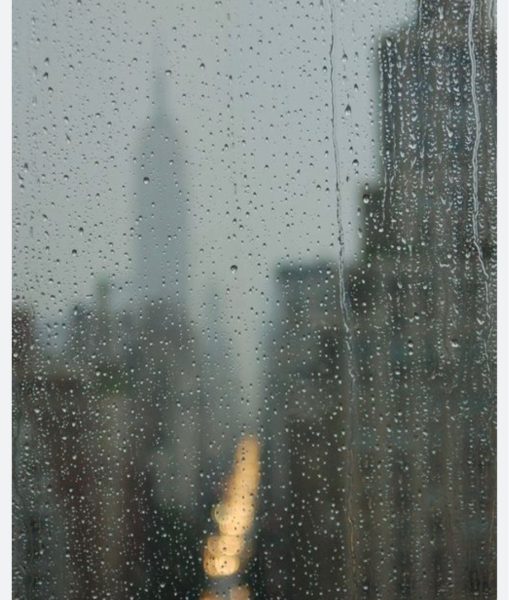

Finally, I get the window seat. This seat never disappoints. I get just the right balance, jumping between worlds whenever I desire – from the chaos of my reality right onto the orderliness of people crossing the street, the tranquility of leaves finally beginning to form after the harsh winter months. In a strange way, I resonate with these trees. Even after months of being challenged by the icy winds and the unforgettable hardships, my straight, unshaken stance will not falter. I still stand upright, looking fresh as new, as though I never even left my hometown to arrive in this strange city where the people don’t look around. They seem too fixated on what’s next.

Did I too become that person — too focused on the future to ground myself in the present moment?

“Would anyone like to share your plans for spring break?” says Mr. Kunhardt at an ever-so quicker pace. This is the last period before we leave off to break; I’ve been fantasizing about this day for way too long. Still gazing through the window, I squint my eyes to remind my musing-self that I must now turn my attention back to the dullness of the classroom. Even the teacher is restlessly fidgeting as he awaits a response, barely holding himself together. I never raise my hand in class. If life was like a classroom in which one must raise a hand to speak, my hands would go numb from uselessness. No one understands me here, I instinctively tell myself. I’m too fragile to face the pain of being misunderstood by everyone in this room. This heavy accent muffles every word into a confusing slop. Several responses are given: Linus is travelling to Berlin to meet his grandparents, while Neima is traveling to attend a national chess competition. Every response manages to beautifully color-in each student’s lines of personality. I look down at my meaningless scribbles, strongly wishing that the rest of the room could read me as vividly as I read each and every one of them…but they cannot.

Suddenly I am tossed into the gates of hesitation. While my mind is pulling me back, away from the claws of embarrassment, my heart pushes forward; I am too captivated by the possibility of sharing an experience I so desperately look forward to. I wiggle my sweaty fingers, activate my wrist, take a deep breath, and finally reveal my palm in a mousy flip of the hand. Without having lifted my arm yet, Mr. Kunhardt shoots his eyes at my pale forehead, his lips squeezed into a fine line. ‘“Yes?” I take a solid second of silence to ensure his gaze is directed towards me. A few long, unpleasant moments elapse while I taste the bitter awkwardness deep inside my throat. “Uh, Ma-HAL-yah?” he clearly struggles to recall my name.

My eyes dilate as though I was just given one nasty slap. All eyes in the room pointed directly at me. Like loaded guns surrounding the target. “Erev Pesach,” I say, looking around me to validate that the message comes through. Instead, I hear chuckles, confusion disperses, and eyebrows are raised. All eyes still on the target. “Pesach?” I repeat, emphasizing every syllable, especially the last one. To everyone around me, I probably sound like a suffocating wolf, articulating the heth and the aiyn, two hebrew letters that powerfully transfigure a delightful word into a seemingly cunning, invasive bark. “Aha…What is that?”, Mr. K asks with a slight tilt of the head. “She means Passover” one kid shouts. I seal my gaping mouth, feeling somewhat relieved yet uneasy about the obvious judgement around the room. Nevermind, I sigh, embarrassingly shuffling in my cold, metal seat .

All my leaves have fallen; the lights are shut.

Kick-opening my room door, I leap onto my stiff bed, covering my face with the soft sheets like a turtle retreating into its shell in the face of danger. Salty tears cool down my cheeks- heated with embarrassment. I wipe the tears away, then blink twice to fix my blurry vision. Papers are dispersed over my wooden desk, Dad appearing several feet away. “What’s wrong, Pashoshit?”, he asks, calling me by the biblical word for a warbler. “I don’t know. This is just too much”, I weep. I tell him about my last class: how isolated and muzzled I feel by everybody’s confusion, their critical glares.

“Would you like an orange?” he inquires after my wretched emotional eruption. Really?, I think irritably, throwing at him a dead stare. “Aba! How could you ignore everything I just said? How can you be so blind? If my life continues on its current path, how will I ever become the happy, successful person you always wanted me to be?”

“Have you ever heard the story Saba Meir told me under his blood orange tree when I was your age?” he asks, referring to my great grandfather. “No,” I reply, thinking back to the only record that captured us together: great grandpa’s affectionate smile pointed at the camera as he held my chubby baby legs. “Before the Holocaust, he found a way to escape to Palestine before the rest of his family was persecuted.” “Oh yeah, I knew that,” I comment. “Well, very shortly after arriving, a bomb went off right next to him, as he was working in an orchard.” I position myself upright, flatten the wet sheets, and settle above the bed. In my mind I picture the scene: the sun blazing in the hot summer day, the dark orange color of the fruit. I hear an explosion and then dead silence punctuated by some screams and calls for help. “He was a lucky survivor, you know? When he woke up at the hospital, he was clueless, completely lost. He was partially deafened by the explosion, but beyond that, he didn’t understand the English spoken by the British soldiers and officials; no one spoke his language.” The loneliness, the dread. My father pauses, sliding his jaw forward. I carefully observe his expression, tracing my eyes down his thick, dark eyebrows, onto the heavy wrinkles around his eyes. His complexion turned peculiar, telling me not to ask questions. Take in the words.

Saba Meir persevered. He didn’t like to talk about his tough past, but this memory was one that always stayed with him. It always stayed with him. He clung onto the smallest beam of light even when all doors seemed shut. He was indeed very lonely but also grateful to survive, while ten siblings later perished in the Holocaust. Drowning in confusion, trapped in dismay. He learned: nothing ever runs smoothly, but one cannot give in to the losses. He let his past troubles nourish his vision for a better future. Many years later, when he finally owned a house, he transformed his traumatic memories by planting a blood orange tree that blossomed with fruit rich in taste, color and… meaning.

Great grandpa is no longer just a photo. He had dreams, he stumbled just like me.

“So, orange?” Dad asks with a smirk on his face. “Yes please,” I murmur. He grabs the fruit, swiftly tossing it over in my direction. I manage to quickly catch it, letting my sorrow fade away. Only now, as I hold the fruit’s weight over my moist skin, I turn attention to an intense hunger. As I gobble up the sweet juice, it cools down the internal chaos. Dad trails his thumb along the packed bumps of the orange peel. “Every time I would visit him, I looked forward to tasting this fruit: it had a vibrant, lush color unlike any other fruit you have ever seen.” He took pride in them. He wanted to remember. The realization grows within me: there will come a time when my own daunting experiences will also turn into a fresh fragrance that will fill me with gratitude for a past of enrichment, for a future to look forward to, and for the infinite opportunities of the here and now.

Daniela is a senior at BASIS Independent Brooklyn. She is very interested in cognitive neuroscience. Outside of school you will find her reading, sketching,...