The History of Murals: Humanity’s First Artform

Living in New York City, one grows accustomed to seeing various forms of art and writing scrawled across practically any clean surface. From stickers to graffiti pieces, art is a key part of New York culture throughout all five boroughs. But quite possibly the most important form of urban art lives among the rest of the illustrations scattered across the walls of the city: murals. They come in many shapes and sizes, and carry a variety of unique themes, but they nevertheless are a crucial form of expression, both for an individual or simply a local community. So where did they originate, and how did they become such a memorable aspect of life here in the city?

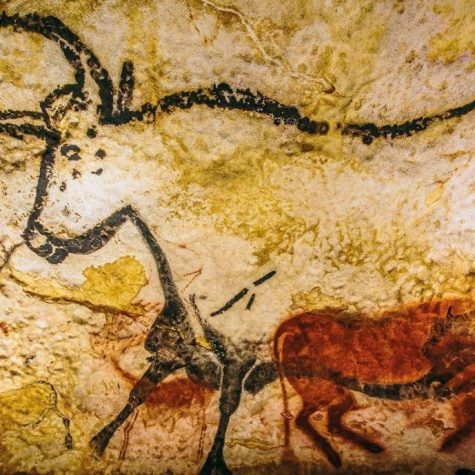

The earliest form of murals dates back to the Paleolithic era, almost 32,000 years, representing some of the oldest

known forms of art in human history. They showcased some of the most simple and primitive examples of human expression, typically displaying a successful hunt or battles with enemy tribes. In a time where paper and stone tablets were still nonexistent, murals were the only way early man could record history and emotions, even if they were vague and simplistic both in design and message.

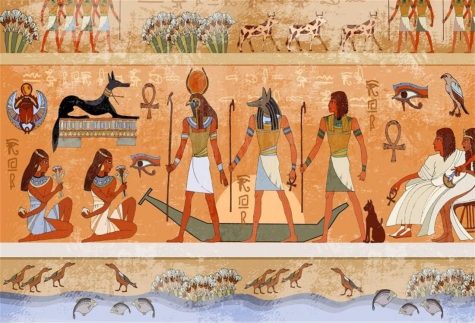

Eventually, as mankind grew and evolved, the introduction of clay tablets and early written language temporarily nullified the need for large-scale murals in order to depict events, and the art world began to spread into more functional

designs, such as pottery, blacksmithing, and weaving, that could be used in the growing civilization as tools. But the mural lived on through the language of the ancient Egyptians, transcribed on the walls of their tombs and palaces, and through the colorful murals painted by the Greeks and Romans that adorned their most holy and powerful buildings, such as the Parthenon or the local baths. In both civilizations, most of these artistic feats were reserved solely for religious purposes, whether to express ancient myths or show the death of a great ruler. However, that would soon change.

Following the Dark Ages, the Italian Renaissance introduced a unique twist on the mural. Starting with the invention of the fresco in the thirteenth century, Renaissance artists maintained the mural’s theme of religious imagery, but created new and interesting interpretations of their true meaning. The reemergence of Greek philosophy made many great thinkers at the time question the Catholic church, and begin rebelling in subtle ways against its domain in Europe. In the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo painted the Papal Master of Ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, as the hellish judge of the underworld in his fresco, “The Last Judgement”, due to Biagio’s complaints about the nudity in Michelangelo’s paintings on the ceiling of the chapel. “The School of Athens”, another notable fresco located in the Vatican and painted by Raphael, portrays some of the greatest scientific and philosophical minds of the Greek era. And “The Creation of Adam” subtly creates the image of a human brain in the form of God and his surrounding angels. The tight religious constraints of the mural had finally begun to loosen, and thus began allowing for more than just holy values to be portrayed through their messages.

Fast forward about 500 year. The year is 1972, New York City. The city was teeming with crime, poverty, and corruption, most of which stemmed from the police department

at the time. New York was in terrible shape, and life in the poorer parts was anything but pleasant. Like many aspects of classic New York culture that originated in poor minority regions of the city, such as breakdancing, rapping, and hip hop, graffiti stemmed from the lack of opportunities and creative outlets that accompanies living in an impoverished neighborhood. Acting as an extension of local allegiance through the formation of “crews”, graffiti soon grew to become more than just vandalism for the sake of public defacement; graffiti artists worked diligently at their craft, filling sketchbooks with intricately designed tags and illustrations in order to be known to the streets.

Graffiti murals honored deceased relatives and friends, pride in one’s nationality, the local community, political and social movements, and even sparked commentary on the legitimacy of art itself. These murals truly reflected an art for the people by the people, as they were done by local residents, were free for anyone walking by to view, and were not bound by the constraints of rich elites, religious figures, or government facilitators commissioning the artwork. It gave poor minorities a voice during a time where their voice was almost entirely ignored, and gave many young people an opportunity to create art during a time where art school was an unattainable dream for their poverty-stricken families.

Nowadays, graffiti is much more widely accepted as an artform, and acknowledged as a renaissance of artistic liberty. Artists like Banksy, Invader, and Shepard Fairey make millions of dollars from auctioning their street art and selling their merchandise, even when their art is still technically illegal. But to this day, murals continue to flourish throughout New York City, whether through graffiti art or through actual paintings. Artists and community organizations throughout the five boroughs use murals to spread messages about politics, public safety, and social issues such as poverty, drug addiction, police brutality, and racism.

These works of art consistently express meaning that is typically more direct than artwork in a museum, mainly because it is aimed at a broader audience of more like minded individuals. Murals can be seen by anyone in a general vicinity, typically a neighborhood population, and since most people are busy going about their lives rather than sitting down and staring at the art, murals must be concise and specific with their purpose. Their meaning usually takes a little deep introspection to understand, making it the perfect art to express much in little time. They act as symbols of a community and its values, and showcase works of art that don’t require the praise and acceptance of fine art critics, tributes to the areas around them and providing a voice to the unheard.

Luca is a senior at BASIS Independent Brooklyn with a passion for drawing; this year, he returns to the team as the Art Director. Luca enjoys...