A Brief History of Systemic Racism in Minneapolis

Photo by Josh Hild on Unsplash

Black Lives Matter Protest in Minneapolis

When the Civil Rights Act was passed in 1964, discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin did not become prohibited, but was rather swept under the rug. Systemic racism is the most common form of racism that exists in America today; it’s complex, hard to see, but deeply ingrained in our systems. And for these reasons, it has always been a particularly stubborn endemic in the city of Minneapolis, despite the city’s reputation as a progressive community.

The widespread coverage of the police killings of George Floyd and Philando Castile has highlighted that Minneapolis clearly has a police problem. However, what many media outlets have failed to cover in Minneapolis is how Black people have not been subject to the economic prosperity that white people have experienced over the last decades.

The “Minnesota Paradox,” a term coined by Samuel L. Meyers Jr., an economist at the University of Minnesota, was made in order to define the harsh segregation and inequality that Black people face in the region. This term raises the question: Why have the Twin Cities become a place where racial inequality is so intense? In order to answer this, we must take a trip back to the years leading up to 1870, the year in which the 15th amendment was passed, which gave African Americans the right to vote. Before the passing of this amendment, the people of Minnesota were able to extend voting rights to Black people, defund segregated schools, and put Black people on juries. However, as a result of this amendment, policymakers in Minnesota became relaxed about the issue, and conditions for Black people, an extremely small minority in Minnesota, didn’t get any better. In fact, in many cases, they got worse.

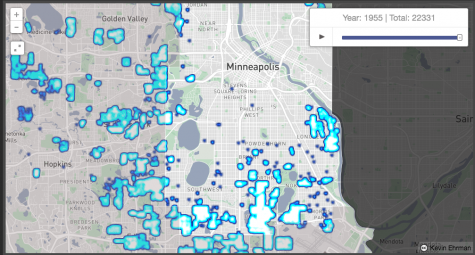

With this neglect of Black people proceeding into the 20th century, segregation got much worse with the increasing introduction of racial covenants in real-estate sales, known as redlining. Redlining was a system in which real estate agents, banks, and other groups, even the U.S. government, denied certain services to large groups of people, many of whom were minority-group members. The website Mapping Prejudice provides an image to help visualize this process. What can be seen on this map is that racial housing covenants have pushed black people into the inner city of Minneapolis until the 1950s. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968, which banned the use of racial covenants, it still leaves lasting impacts on Black communities in Minneapolis more than 50 years later. Although this process is now considered unethical and illegal, it still happens, just in a more disguised fashion. In fact, redlining is in large part why roughly 75% of white families in the Twin Cities own their homes, but only about 25% of Black families own theirs. This also explains why white families have acquired much more wealth than Black people have, as they can invest in their homes and enjoy the appreciation in their value.

With this neglect of Black people proceeding into the 20th century, segregation got much worse with the increasing introduction of racial covenants in real-estate sales, known as redlining. Redlining was a system in which real estate agents, banks, and other groups, even the U.S. government, denied certain services to large groups of people, many of whom were minority-group members. The website Mapping Prejudice provides an image to help visualize this process. What can be seen on this map is that racial housing covenants have pushed black people into the inner city of Minneapolis until the 1950s. Although redlining was outlawed in 1968, which banned the use of racial covenants, it still leaves lasting impacts on Black communities in Minneapolis more than 50 years later. Although this process is now considered unethical and illegal, it still happens, just in a more disguised fashion. In fact, redlining is in large part why roughly 75% of white families in the Twin Cities own their homes, but only about 25% of Black families own theirs. This also explains why white families have acquired much more wealth than Black people have, as they can invest in their homes and enjoy the appreciation in their value.

Black people make up about 20% of Minneapolis’ population, and represent one of the fastest-growing segments of the population. Yet, Black people still aren’t expanding their footprint beyond the small concentrated areas they populate in the Twin Cities, where much of the affordable housing can be found. Furthermore, because the majority of Black families don’t own their homes, getting out of these redlined areas, which are infused with high crime and low standards of living is extremely hard.

Redlining has made the playing field uneven for Black people as it has made their communities more easily identifiable to employers, banks, real estate agents, and the U.S. government. Because of this, Black people are consistently denied high-paying jobs, mortgages from banks, and even recently, small business loans from the U.S. government. Systemic racism is a threat to social equity and equality in our country, and Minneapolis is a perfect example of how this can be masked with the label of a “progressive” city.

Charlie is a senior at BASIS Independent Brooklyn with a love for football and basketball. Recently, he has shifted his interests to politics and journalism....